Ethics statement and sample collection

Snap-frozen gastric biopsy samples were obtained from three sources:

-

1.

Multisite sampling performed on gastrectomy specimens removed as part of either gastric cancer treatment or bariatric surgery. Written informed consent for participation in research and publication of data was obtained from all donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and protocols approved by the relevant research ethics committees (RECs): (1) source country approval by the IRB of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority of Hong Kong West Cluster, REC approval reference number UW14-257; (2) UK NHS REC approval from the West Midlands-Coventry and Warwickshire REC, approval number 17/WM/0295, UK Integrated Research Application System project ID 228343.

-

2.

Multiregion gastric biopsies from transplant organ donors with informed consent for participation in research and publication of data obtained from the donor’s family as part of the Cambridge Biorepository for Translational Medicine programme (UK NHS REC approval reference number 15/EE/0152; approved by NRES Committee East of England—Cambridge South).

-

3.

Gastric samples obtained at autopsy from AmsBio (commercial supplier). UK NHS REC approving the use of these samples: London-Surrey Research Ethics Committee, REC approval reference number 17/LO/1801.

Further metadata for donors can be found in Supplementary Table 1, and metadata for all samples can be found in Supplementary Table 2 (WGS) and Supplementary Table 3 (targeted panel sequencing). No statistics were used to predetermine sample size, nor did we use any blinding or randomization.

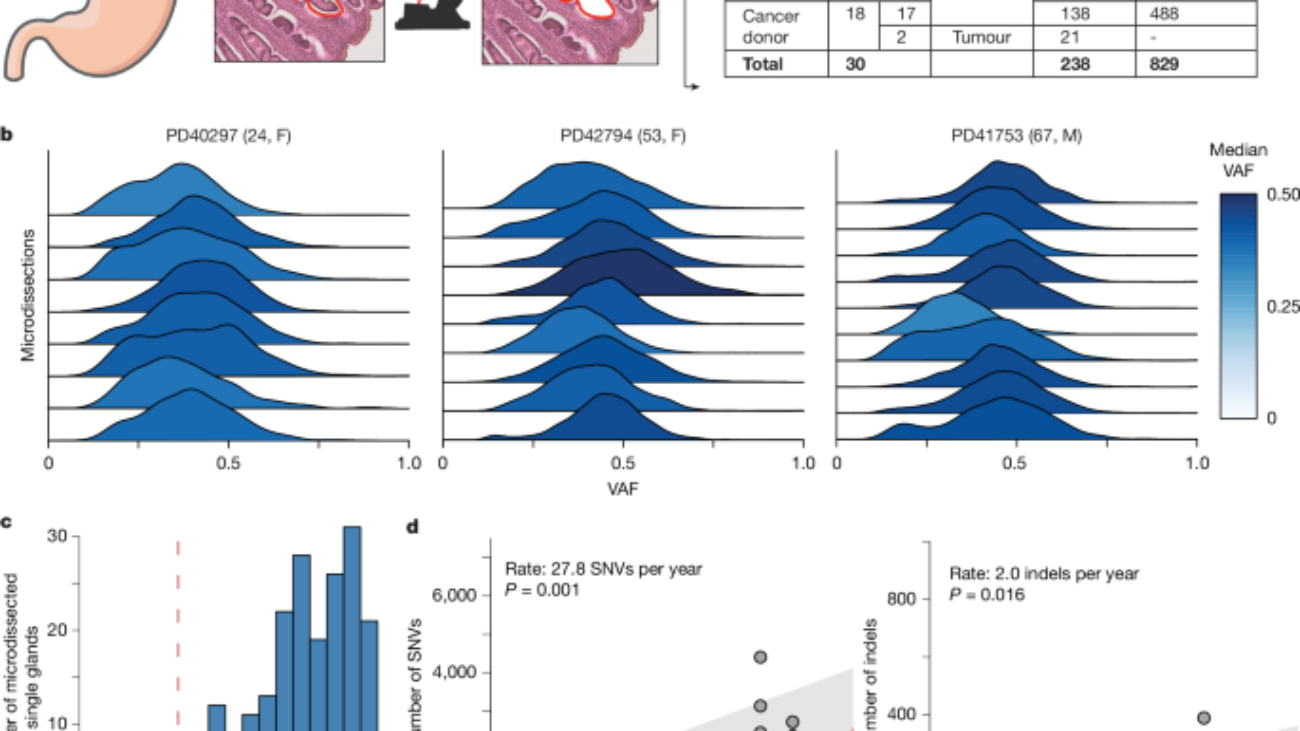

Laser capture microdissection and low-input DNA sequencing

Gastric tissue biopsies were embedded, sectioned and stained for microdissection as described in detail previously2. DNA libraries were constructed from microdissections using enzymatic fragmentation and subsequently submitted for WGS or targeted panel sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten or NovaSeq platform. Average sequencing coverage can be found in Supplementary Table 2 (WGS) and Supplementary Table 3 (targeted panel sequencing).

We used a custom Agilent SureSelect bait set to capture the exonic regions of 321 cancer-associated genes (listed in Supplementary Table 7).

DNA sequence processing, mutation calling and filtering

DNA sequences were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome by the Burrows–Wheeler algorithm32. SNVs and indels were called against the reference genome using CaVEMan33 and Pindel34, respectively. CNVs and structural variants were called using GRIDSS35 and ASCAT36 and are listed in Supplementary Table 4 (CNVs, both GRIDSS and ASCAT) and Supplementary Table 5 (intrachromosomal structural variants, GRIDSS only).

Beyond the standard postprocessing filters of CaVEMan, we removed variants affected mapping artefacts associated with the Burrows–Wheeler algorithm by setting the median alignment score of reads supporting a mutation as greater than or equal to 140 (alignment score median (ASMD) ≥ 140) and requiring that fewer than half of the reads were clipped (clipping median (CLPM) = 0).

We force-called the SNVs and indels that were called in any sample across all samples from a given donor, using a cut-off for read mapping quality (30) and base quality (25), before applying the Sequoia pipeline37 for mutation filtering and phylogeny reconstruction.

As part of the mutation filtering, germline variants were removed using a one-sided binomial exact test on the number of variant reads and depth present across largely diploid samples, as previously described3,8. Resulting P values were corrected for multiple testing with the Benjamini–Hochberg method, and a cut-off was set at q < 10−5. To filter out recurrent SNV and indel artefacts, we fitted a beta-binomial distribution to the number of reads supporting variants and the total depth across samples from the same individual. For every indel or SNV, we estimate the maximum-likelihood overdispersion parameter (ρ) (ranging the value of log10(ρ) from −6 to −0.05 in steps of 0.05). As artefactual variants appear in random reads across samples, they are best captured by low overdispersion, whereas true somatic SNVs and indels will manifest with high VAFs in some but are completely absent from other samples and are therefore highly overdispersed. To distinguish artefacts from true variants, we used ρ = 0.1 as a threshold for SNVs and ρ = 0.15 for indels, below which variants were considered to be artefacts. This filtering approach is an adaptation of the Shearwater variant caller38.

We used a truncated binomial mixture model to model each whole-genome sample as a mixture of clones, determine the underlying VAF peaks and the corresponding clonality of the sample as previously described3,37. The truncated distribution is necessary to reflect the minimum number of reads that support a variant (n = 4) that is imposed by variant callers such as CaVEMan.

Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using Sequoia37, which uses a maximum parsimony framework as implemented in MPBoot39, with default settings. Mutation mapping to branches was done using the treemut R package.

Mutation rate analysis

To correct for the confounding of sequencing depth and detected number of mutations, we corrected the observed mutation burden by dividing over the estimated sensitivity. The sensitivity was estimated as the probability of observing a variant in at least four reads given the underlying coverage distribution per sample and the observed variant allele frequency peak per sample. The mean estimated sensitivity was 0.95 and the median 0.97. Raw and adjusted mutation burden estimates, for both indels and SNVs, are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

To estimate the mutation rate in normal gastric epithelium, we used a linear mixed-effects model, with age as a fixed effect and the donor as a random effect, on mutation burden estimates from gastric glands of non-cancer donors:

-

1.

Burden ~ (distributed as) Age + (1|Donor)

We assessed the effects of chronic inflammation (CI, coded as absent or mild versus moderate or severe) and IM (absent or present) by using these alternative models:

-

2.

Burden ~ Age + CI + (1|Donor)

-

3.

Burden ~ Age + IM + (1|Donor)

-

4.

Burden ~ Age + IM + CI + (1|Donor)

Models 2 and 3 significantly outperform model 1 (P < 2.2 × 10−16), and although model 4 outperforms model 2 (P < 2.2 × 10−16), it does not significantly outperform model 3 (P = 0.11). Therefore, presence or absence of IM and age predict mutation burden the best.

To test the effect of gastric site on the mutation rate, we included site-specific age relations in the mixed-effects model:

-

5.

Burden ~ Age:Site + IM + (1|Donor).

This model did not significantly outperform model 2 (P = 0.4547).

Telomere length analysis

The average telomere length for WGS samples was estimated using the telomerecat algorithm40, which uses the prevalence of the TTAGGG telomeric repeat in reads. Samples sequenced on the NovaSeq platform were excluded from this analysis, as we previously observed discordant results1, such as telomere lengths of 0 bp, from such samples.

Similarly to the mutation burden analysis, we used a linear mixed-effect model to assess the effects of age, IM and chronic inflammation on telomere length:

-

1.

Telomere length ~ Age + (1|Donor)

-

2.

Telomere length ~ Age + CI + (1|Donor)

-

3.

Telomere length ~ Age + IM + (1|Donor)

-

4.

Telomere length ~ Age + IM + CI + (1|Donor)

Models 2 significantly outperforms model 1 (P = 0.0005), and model 4 does not significantly outperform model 2 (P = 0.14). Including IM annotation does not improve the model fit. Therefore, chronic inflammation and age predict telomere length the best.

Mutational signature analysis

To identify possibly undiscovered mutational signatures in human placenta, we ran the hierarchical Dirichlet process (HDP) package (https://github.com/nicolaroberts/hdp) on the 96 trinucleotide counts of all microdissected samples, divided into separate branches of the phylogenetic trees. To avoid overfitting, branches with fewer than 50 mutations were not included in the signature extraction. HDP was run with the different donors as the hierarchy, with 20 independent chains, 40,000 iterations and a burn-in of 20,000.

The resulting signatures from HDP were further deconvolved into linear combinations of known COSMIC reference signatures (v.3.4) using an expectation-maximization mixture model. The deconvolution is accepted if the resulting linear combination of reference signatures has a cosine similarity to the original, extracted signature that exceeds 0.90. This resulted in the deconvolution of the HDP signatures into reference signatures SBS1, SBS2, SBS3, SBS5, SBS13, SBS17a, SBS17b, SBS18, SBS28, SBS40a and SBS40c. These signatures were then fitted to all observed SNV counts from individual branches using SigFit41. Signature exposures per sample can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Of note, SBS5 and SBS40 have relatively flat and featureless mutation profiles, can be difficult to separate from each other and are therefore combined in analyses, as in previous reports1,42.

The fold increase of specific mutational signatures in metaplastic glands compared to non-metaplastic glands was estimated by

-

1.

Calculating the observed number of mutations incurred by each signature by multiplying the sensitivity-corrected mutation burden with the estimated signature exposures per sample.

-

2.

Calculating the expected number of mutations incurred by each signature by multiplying the expected mutation burden, given the age of the donor and the average mutational signature distribution of all non-metaplastic glands of that donor. The latter accounts for any donor-specific differences in mutational signatures that may be present.

-

3.

Dividing the observed over the expected mutation numbers per signature.

The procedure for indel signature extraction was performed identically to that listed above for SNVs. The five resulting HDP indel signatures were deconvolved into COSMIC reference signatures ID1, ID2, ID5, ID6, ID9, ID12 and ID14. HDP indel signature 5, a noisy signature typified by large deletions, was not decomposed further as no combination of reference signatures yielded a high enough cosine similarity to the extracted signature. As SigFit41 is not compatible with indel signatures, the exposure to HDP signatures was converted to the exposure to reference signatures using the estimated signature proportions from the deconvolution. Signature exposures per sample can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Selection analysis and driver annotation

We used the dNdScv27 R package to identify genes under positive selection. For genes in the targeted panel, we combined the data from both the WGS data and the targeted sequencing data. As the difference in coverage/clonality between the WGS data and the targeted sequencing data affects both non-synonymous and synonymous mutations, this mixed data can be safely fed into dNdScv, as applied previously12. To avoid overestimating the occurrence of mutations due to sampling the same clone in several microdissections, we only count a specific mutation once per donor. Genes with a q-value below 0.1 were considered to be under selection, which amounted to ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, CTNNB1, EEF1A1, LIPF and KDM6A.

In addition, we used the WGS data to look for signs of selection outside of the genes included in the panel. This did not yield any further genes under selection.

To identify mutations in genes that are associated with cancer but did not appear in the positive selection analysis, we reviewed all mutations for canonical cancer driver mutations and annotated likely candidates. In brief, this involved annotating hotspot mutations in oncogenes and inactivating mutations (nonsense, missense and frameshift indels) in tumour suppressor genes through interrogation of the COSMIC database. Annotated driver mutations are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Estimate of proportion of epithelium with driver mutation

To estimate the proportion of gastric epithelium that harboured a driver mutation, we relied on the measurements of area of microdissections and the estimated cell fraction that harbours a driver mutation in a sample. This cell fraction is straightforwardly obtained by multiplying the VAF of a mutation by the local ploidy (1 for sex chromosomes in male donors, 2 otherwise). Multiplying mutant cell fractions with the area of epithelium sampled gives an estimate of the area of mutant epithelium. By summing up the total area of mutant epithelium and dividing by the total epithelial area sampled, we arrive at an estimate of the fraction of gastric epithelium that has been colonized by a clone with a driver mutation. For this analysis, we used both disrupting (missense, nonsense, frameshift and splicing) mutations in genes identified as under selection by dNdScv and manually annotated driver mutations (see the previous section).

Note that this approach assumes that the entire microdissected area consists of gastric epithelium. Any contaminant cell type will lower the VAF of mutations in gastric clones and therefore reduce the estimated mutant sizes. Therefore, the estimated proportion of epithelium can be slightly underestimated.

The role of age, chronic inflammation and IM on the proportion of gastric epithelium was evaluated using a set of linear models:

-

1.

Mutant_proportion ~ Age

-

2.

Mutant_proportion ~ Age + CI_grade

-

3.

Mutant_proportion ~ Age + IM_proportion

These models were compared against each other using a two-sided ANOVA test. Model 2 was a significantly better fit than model 1 (P = 0.002). Model 3 was not a significant improvement over model 1 (P = 0.86). The effect of age was significant in all models, and severe chronic inflammation was significant in model 2 (P = 0.001).

CNV timing

Assuming a constant mutation rate, the acquisition of large copy-number duplications, such as trisomies or events causing copy-number neutral loss of heterozygosity, can be timed by comparing the proportion of SNVs acquired before and after the duplication. These proportions can be estimated by clustering SNVs on the basis of their VAF. As previously, we used a binomial mixture model, using the counts of variant-supporting and total reads, to estimate the fraction of duplicated and non-duplicated mutations. Mutation clusters were assigned to be either duplicated or non-duplicated on the basis of the expected VAF from the CNV. For example, for a trisomy, the two VAF clusters would correspond to two different copy-number states: 0.66 (duplicated, mutations on two out of three copies) and 0.33 (non-duplicated, mutations on one out of three copies).

From the duplicated (PD) and non-duplicated (PND) proportions, the total copy number (CNtotal and the duplicated copy number (CNdup), the timing of the CNV (T) can then be estimated as follows:

$$T=\frac\rmCN_\rmtotal{\rmCN_\rmdup+\fracP_\rmNDP_\rmD}$$

The value of the CNV timing will be between 0 and 1, which—in the case of phylogenetic trees used here—corresponds to the beginning and end of the branch on which the CNV was acquired. To obtain a confidence interval around the single timepoint estimate, we used an exact Poisson test on the rounded duplicated and non-duplicated mutation counts.

Identifying trisomy 20 in panel sequencing data in PD40293

Calling copy-number variation de novo from targeted panel sequencing is challenging due to the sparse sampling of the genome and uneven capture by baits, resulting in a very uneven coverage landscape. However, we used the paired WGS data to effectively assign SNPs on chromosome 20 to either parental haplotype, as these SNPs would have differential VAFs in the whole-genome sequenced samples with trisomy 20 (seven out of 12 samples) in PD40293, the donor with the most widespread recurrence of trisomy 20.

To identify the panel-sequenced microdissections with likely trisomy 20, we quantified the count data (reads supporting SNP and total reads) for phased SNP sites on chromosome 20. Using a likelihood ratio test, we quantified whether it was more likely that the two groups of phased SNPs were drawn from one binomial distribution with underlying probability of the mean total VAF across both haplotypes (diploidy) or two binomial distributions with a different probability underlying each of the two haplotypes (aneuploidy). To reduce noise, only SNP sites with more than five reads were used in this analysis. Resulting P values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Besides significant differences, samples also needed to show a high enough difference between mean VAFs of the two haplotypes to be considered showing evidence of trisomy 20 (0.1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Source link

Add a Comment