Children are always asking “Why?” As they experience things for the first time, it’s natural to want to find out more. But as children grow into adults, they often dismiss something new that challenges their experience and understanding.

This is what happened to me when I discovered a source of oxygen production in the deep sea—but ignored it for nine years.

In 2013, I was conducting experiments to measure seafloor carbon cycling in the Clarion-Clipperton zone of the Pacific Ocean in 2013. I deployed a lander system (a remote-operated platform used to carry scientific equipment) to a depth of 4,000 meters and it came back with bubbles inside it. This was highly unusual, so two years later, when we returned to the same site, I took some optodes (oxygen sensors) with me.

These are designed to measure oxygen consumption, but instead they were showing me oxygen production, the exact opposite of what I was expecting. Instead of questioning why I was getting these results, I dismissed the reading as the result of a faulty sensor.

We are all taught from very early on in our education that oxygen is only produced through photosynthesis and that requires light—something in short supply at thousands of meters below the sea surface. It took me until 2021, when I measured oxygen production with a second method, that I realized we’d found something exceptional: dark oxygen—oxygen that’s produced without sunlight.

In the summer of 2024, my team and I published our findings in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The discovery of dark oxygen has shifted our understanding of the deep sea and potentially life on Earth. But we still don’t know for sure how this oxygen is produced, and to what extent, and whether it is ecologically significant to the deep-sea ecosystems where it happens.

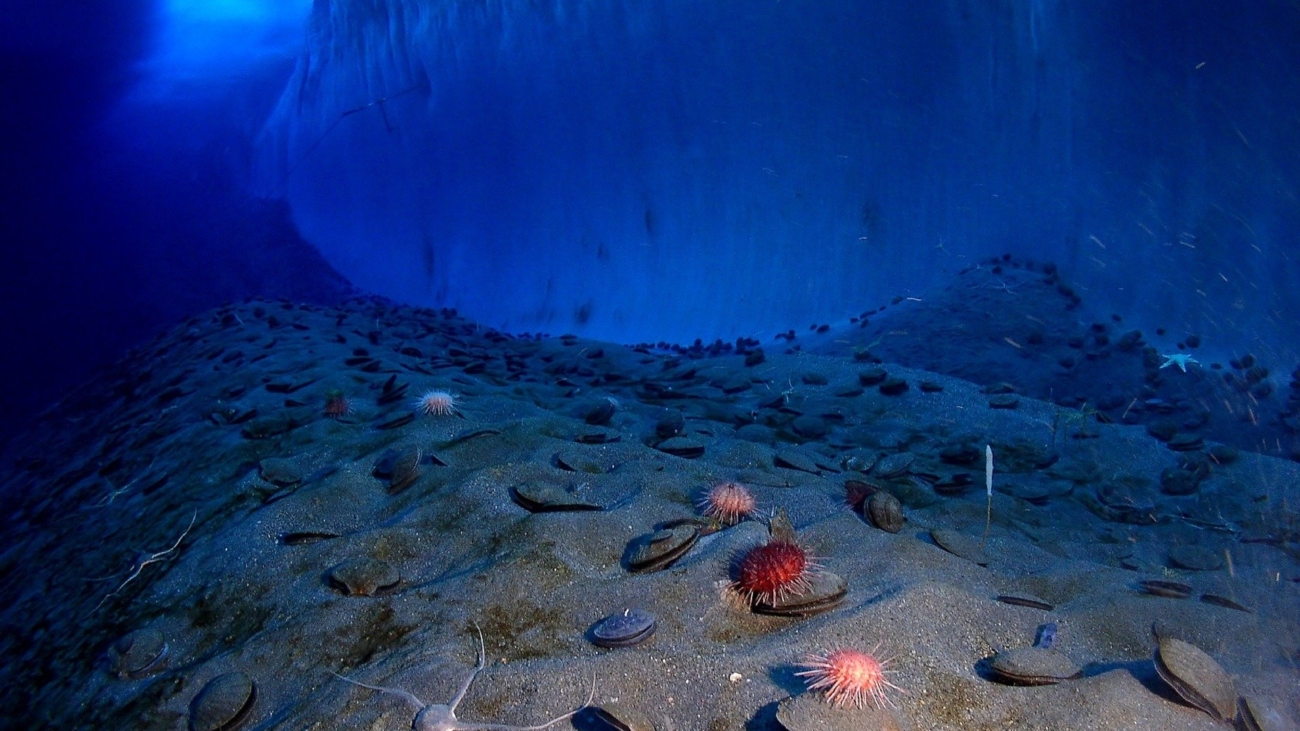

In our paper, we suggest that the source could be polymetallic nodules, rock-like formations composed of lots of different metals, including manganese, which can create differences in electrical potential when interacting with seawater.

We proposed that these could produce a voltage sufficient to split the seawater into hydrogen and oxygen. A new Chinese study has just shown that oxygen can potentially be produced when these manganese nodules are forming.

More ‘why’ questions

This year we will probe some of these scientific questions. If we show that oxygen production is possible in the absence of photosynthesis, this discovery would change the way we look at the possibility of life on other planets too.

Indeed, we are already in conversation with experts at NASA who believe that dark oxygen could reshape our understanding of how life might be sustained on other ocean worlds like Enceladus and Europa, moons that have ice crusts that limit sunlight penetration to the ocean below.

We’re also in the process of analyzing the potential of dark oxygen in the central Pacific Ocean and developing purpose-built and autonomous landers, or rigs. This will be the UK’s first opportunity to sample below depths of 6,000m.

These vehicles will carry specialist instrumentation to depths of 11,000 meters, where the pressure is more than one metric ton per square centimeter (that’s equivalent to 100 elephants sitting on top of you).

We will investigate whether hydrogen is released during the creation of dark oxygen, and whether it is used as an energy source for an unusually large community of microbes in parts of the deep ocean. We also want to find out more about how climate change might impact biological activity in the deep sea.

This project is the first of its kind to directly explore these processes. My team will be able to study the deep seafloor into the hadal zone, an area which reaches 6,000–11,000 meters in depth and makes up around 45% of the entire ocean. This habitat, full of deep ocean trenches, is still poorly understood.

The discovery of dark oxygen clearly has potential implications for the deep-sea mining industry. Deep-sea mining would extract polymetallic nodules that contain metals such as manganese, nickel and cobalt, which are required to produce lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and mobile phones.

We don’t yet know how an industry such as this would affect the seabed, but our research over the coming years should help to answer many of the questions posed and perhaps better inform where the seabed should be more protected from deep-sea mining. One thing is for sure: whatever we find, I’ll try and feed my child-like sense of enthusiasm and be sure to ask “Why?”

More information:

Andrew K. Sweetman et al, Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor, Nature Geoscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Citation:

Team discovers ‘dark oxygen’ on the seafloor (2025, March 23)

retrieved 23 March 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-03-team-dark-oxygen-seafloor.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Add a Comment