If things are best judged by their enemies, not their friends, then Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) just received a major tick of approval! The powerful American lobby group for pharmaceutical giants — PhRMA — is urging the Trump administration to place tariffs on Australian pharmaceutical exports because the PBS is an “egregious and discriminatory” trade instrument.

While not perfect, the PBS is an example of successful public policy. Beginning in 1948, it provided free medicines for pensioners and 139 medicines deemed “life-saving and disease-preventing” for all residents, with the government picking up the bill. Today, it subsidises 930 medicines to the tune of $17.7 billion a year. It ensures Australians can access effective drugs based on medical need, not ability to pay. It’s also cost-effective: the PBS only lists drugs with proven safety and efficacy and without cheaper alternative therapies, and the government negotiates an affordable price with the companies.

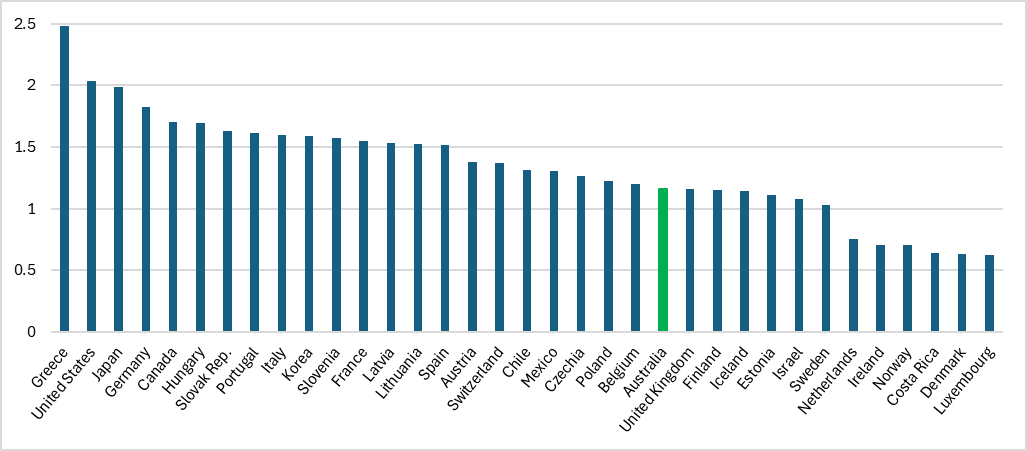

Not only does it generate an immense consumer surplus, but the PBS is also a key reason why our pharmaceutical spending is at more sustainable levels compared to our OECD peers.

To be clear: PhRMA wants Trump to punish Australian pharmaceutical companies — our third-largest exporters to the US — because we have a successful, national pharmaceutical procurement and pricing policy that puts the interests of patients and population health first. Ironically, the proposed tariffs would ultimately make medicines even more expensive for US patients.

But wait, it gets even more absurd. PhRMA is simultaneously lobbying Trump to exempt pharmaceuticals from European Union tariffs, partly to reduce the likelihood of retaliatory tariffs on US medicines, but predominantly to prevent patients from “paying the price” for costlier drugs. Honestly.

Safety first

PhRMA has long despised the PBS for two reasons.

First, it has strict criteria regarding the safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of drugs compared to viable alternatives, which extends the time it takes to approve a drug. Drugs take longer to be listed on the PBS than with payers in some countries, partly because the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) must also assess the drug from a safety perspective (the PBS focuses more on its cost-effectiveness).

There’s good reason for this: it saves lives. Rushed approvals may be good for short-term industry profits but can have disastrous consequences for patients. Vioxx, an anti-inflammatory, was found to cause heart attacks and strokes. It was linked to the deaths of about 300 Australians before it was withdrawn. In the US — where its approval was expedited — the toll was estimated at around 50,000 deaths.

Waiting until a new drug is in routine use elsewhere can avoid such harm. US approval for leukaemia drug ponatinib was based on a clinical trial that was not only unrepresentative (only 449 participants) but also used so-called surrogate outcomes — substitute metrics used to infer actual patient outcomes like survival, which take longer to measure. Once in clinical use, ponatinib was found to cause serious adverse events in a considerable number of patients and was recalled. Australia ended up approving ponatinib but with a prominent warning on the label.

Holding off approval can also mitigate the effects of deliberate malfeasance. The manufacturer of dabigatran, an anticoagulant, withheld safety information in its submission to the US regulator. Consequent mis-dosing in clinical use led to severe bleeding in some patients. Australian regulators had more time to recommend more conservative dosing, avoiding considerable patient harm.

Safety simply must come first; the consequences of failure far outweigh the benefits of faster access. Slower, more comprehensive consideration might temporarily deny a few patients treatment, but will potentially save the lives — and reduce the suffering — of many more.

Value for money

The second reason for the hatred of the PBS is the familiar trope of supply-side medical lobbies against single-payer models: it’s much harder to strong-arm a national agency than a health insurer, which competes with other insurers on what its policy does and doesn’t cover. The PBS negotiates on behalf of all Australians. This gives it far more leverage to procure the lowest price and the best value.

Readers may recall that PhRMA was extremely unhappy with the Biden administration for permitting Medicare (the largest medical insurer in the US) to negotiate prices for a modest number of drugs as part of its 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Its dummy spit included threats that innovation would wither, leading to “fewer treatments and cures — particularly for tough illnesses like cancer and Alzheimer’s disease”.

This is akin to saying you have to pay top dollar for our crappy stuff so that we can — occasionally — develop a blockbuster (for which we’ll charge you a lot more). In any case, it seems that researchers didn’t get that memo, with advances in cancer, dementia and genetic therapy continuing unabated since the IRA became law.

What will Trump do?

It’s easy to see why PhRMA might pull this manoeuvre right now. Predicting how Trump will respond is more difficult, especially given the lobby’s dissonant position on pharmaceuticals coming from Europe (nothing had been announced at the time of writing). The question may be irrelevant. The savage funding cuts to biomedical research (the wellspring of most pharmaceutical innovation) may obliterate the industry anyway, unless courts can mitigate the scale.

The first time around, Trump promised to target high drug prices in the US and set some things in train to achieve this. This time around he has repealed some Biden-era initiatives to lower drug prices but hasn’t yet touched the IRA. Then again, Trump’s zero-sum mentality towards public policy may lead him to think that Australia’s success somehow directly translates to America’s loss… or perhaps he’ll think that the PBS was “formed to screw the United States”. It’s anyone’s guess.

The attack on the PBS — however illogical and brazen — is a compliment, and it’s good to see bipartisan support for the scheme in Canberra. For what it’s worth, Australia is ranked 5th on life expectancy at 65 (the US is 28th) so we must be doing something right. Perhaps the pharmaceutical industry should redirect some of the US$390 million it spends on lobbying US politicians each year to develop more therapies worth paying high prices for?

Have something to say about this article? Write to us at [email protected]. Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Source link

Add a Comment