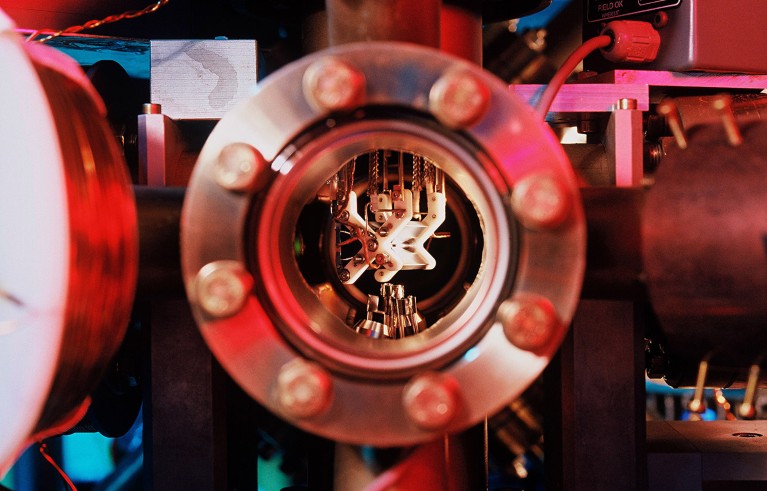

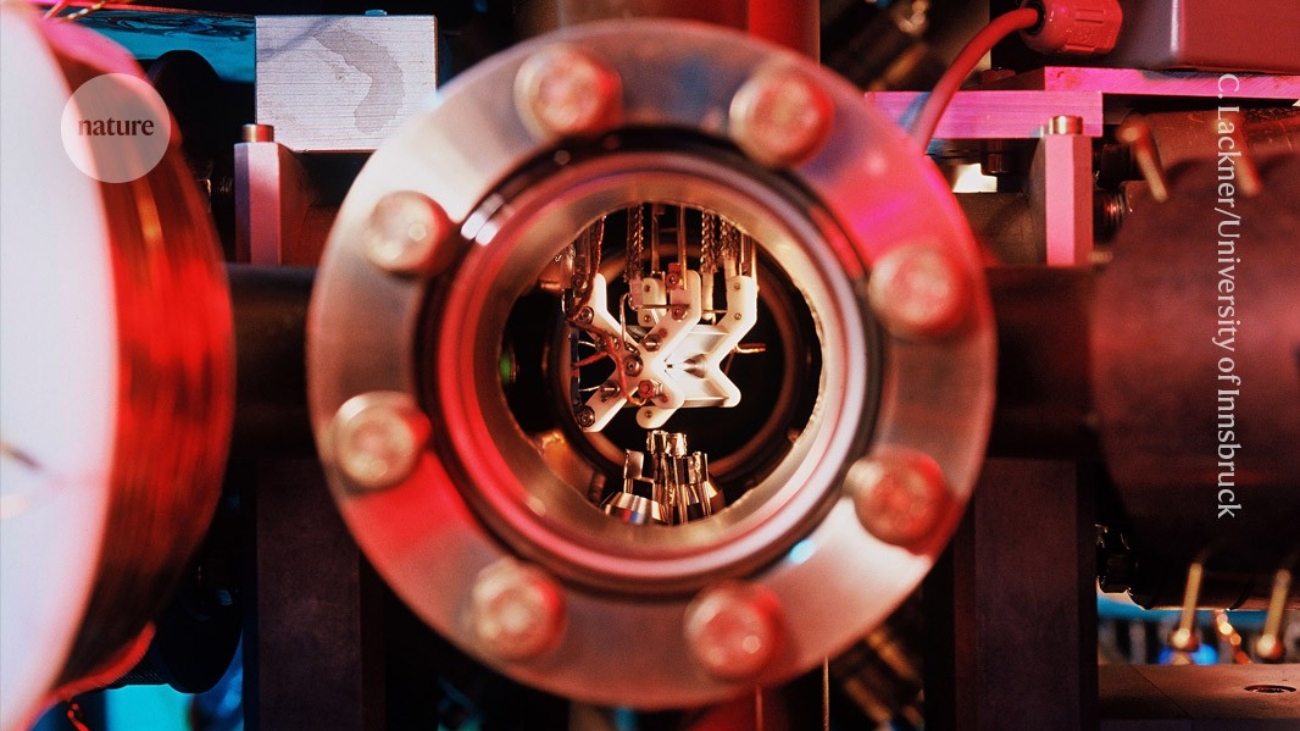

Part of the quantum computer at Innsbruck University, on which researchers did simulations using qutrits and ququints. Credit: C. Lackner/University of Innsbruck

Quantum computing has so far nearly always involved calculating with qubits — quantum objects that can take the value ‘0’ or ‘1’, like ordinary computer bits, but that can also be in a range of combinations of 0 and 1. Now researchers are producing the first applications of ‘qudits’: units of information that offer combinations of three or more simultaneous states.

In a paper published on 25 March in Nature Physics1, physicists describe how they used ‘qutrits’ and ‘ququints’ — qudits with three and five states respectively — to simulate how high-energy quantum particles interact through an electromagnetic field. The work follows a result published in Physical Review Letters (PRL) in September2 that reproduced the behaviour of another quantum field, that of the strong nuclear force, using qutrits.

Quantum stock whiplash: what’s next for quantum computing?

Such simulations of quantum fields are seen as one of the most promising applications of quantum computers, because these machines could predict phenomena in particle colliders or chemical reactions that are beyond the abilities of ordinary computers to calculate. Qudits are naturally suited to this task, says theoretical physicist Christine Muschik, a co-author of the Nature Physics paper who also pioneered such simulations with qubits in 20163 together with colleagues at the University of Innsbruck, Austria. “If I could go back in time to my old self, I would tell her: why waste time with qubits?” says Muschik, who is now at the University of Waterloo, Canada.

“This qudit approach is not a solution to everything, but it helps you when it is suitable to the problem,” says Martin Ringbauer, an experimental physicist at the University of Innsbruck and the lead author of the paper.

More generally, qudits can help to make calculations on a quantum computer more efficient and less error-prone, at least on paper. With qudits, each computational unit that previously encoded a qubit — such as a trapped ion or a photon — can suddenly pack in more information, helping the machines to scale up faster. But the tactic is less mature than approaches based on qubits, and the devil could be in the detail. “Qudits are also more complicated to work with,” says Benjamin Brock, an experimental physicist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

System tweaks

In most types of quantum computer, the qubits that researchers use are two possible states of a system that would naturally have many more states. Such a system could therefore host qudits as well. “Existing qubit processors such as those of IBM and Google can already be operated as qutrits, and would require minor tweaks to operate as high-dimensional qudits,” says Machiel Blok, a physicist at the University of Rochester, New York. (Blok and his team have done experiments in their laboratory in which superconductors encoded qudits of up to 12 levels4.)

Quantum-computing approach uses single molecules as qubits for first time

For their quantum-field simulations, the authors of the PRL paper encoded qutrits on a superconducting quantum chip that IBM makes available to researchers, and that is normally used as a qubit machine. Ringbauer, Muschik and their colleagues used excited states of calcium ions to represent their five-level ququints. A ququint is a natural way to represent a field that can be in a lowest-energy state (with value 0) or have positive or negative values from −2 to +2 at any point in space, Muschik says.

Source link

Add a Comment