South Caucasus correspondent

Reuters

ReutersMost of the villagers in Chorvila in north-west Georgia adore Bidzina Ivanishvili, their proudest son who’s widely seen as the country’s real man in power.

It’s a picture postcard settlement where the roads are good, the houses well-maintained and there are plenty of blue and yellow flags of the ruling Georgian Dream party.

“All this area where you can see new houses and roads was made by our man. There was nothing without him and he did everything for us,” says resident Mamia Machavariani, pointing at the village from a nearby forest.

Ivanishvili founded Georgian Dream (GD) and the party has been in power for 12 years.

For more than four months, Georgians have taken to the streets across the country to accuse Ivanishvili’s party of rigging elections last October and accusing GD of trying to move the country away from its path to the EU and back into Russia’s sphere of influence.

GD denies that and in Chorvila you will not find anyone with a bad word to say about its billionaire son.

Ivanishvili made his fortune in Russia in the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, first by selling computers before he acquired banks and metal assets. He returned to Georgia in 2003.

Every newlywed couple in Chorvila receives a cash gift of $3,000 (£2,300) from Ivanishvili, according to Temuri Kapanadze, who teaches history at the village school where Ivanishvili went as a boy.

Unlike most schools in rural Georgia, it has its own swimming pool and an indoor basketball court.

“He reconstructed the hospital, he built two churches, he fixed all the roads, he made all roofs across the region,” Temuri says.

“I personally received a refrigerator, TV, a gas stove and for five years Mr Bidzina has been helping us by paying 200 laris (£55) every month.”

Here they accuse the opposition of orchestrating the pro-EU anti-government protests and using young people as their “tools”.

“We also want Europe but with our traditions, and that’s what the government wants too,” says resident Giorgi Burjenidze. “We are a Christian country, and our traditions means that men must be men, and women must be women. President Trump thinks like us too.”

The view that Europe has been trying to impose values alien to Georgian traditions, such as gay rights, is often repeated by state ministers and pro-government media.

They have also been dismissive of the daily protests sparked by the Georgian Dream’s decision to suspend talks with the European Union on the country’s future membership.

“Fire to the oligarchy” has become one of the main slogans at the ongoing protests to address what people say is the overwhelming influence of Bidzina Ivanishvili on the country’s politics.

“Georgia currently is ruled by an oligarch who has a very Russian agenda,” says Tamara Arveladze, 26, who has joined the protests in the capital Tbilisi almost every day, to fight what she sees as Ivanishvili’s overwhelming influence.

“He owns everything, all the institutions and all the governmental forces and resources. He sees this country as his private property, and he is ruling this country as if it were his own business.”

EPA

EPALast month, Tamara and her boyfriend were caught up in an incident which was captured on mobile phones and went viral. They were driving towards the protest site, and shouted the words “fire to the oligarchy” when a number of masked policemen surrounded the car and tried to break in.

“It happened in seconds, but it felt like hours. I was shocked how aggressively they were trying to do this, if they’d happened to take us out of the car I don’t know what would have happened.”

Tamara’s boyfriend has had his driving license revoked for a year and could face a jail term for swearing at police. She has been fined $3,600, an enormous sum in Georgia, where the average monthly salary is closer to $500.

Since the disputed parliamentary election, criticised by international observers, the Georgian opposition has been boycotting the parliament, leaving the ruling Georgian Dream to rubber stamp any proposed changes to law.

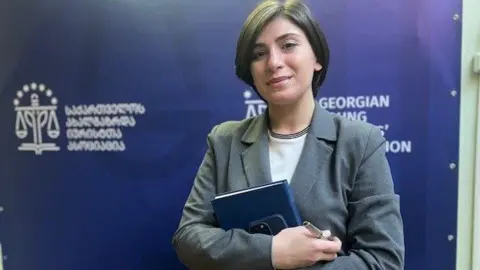

“We are witnessing the abuse of the law-making,” says Tamar Oniani, human rights programme director at the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association.

“First it was banning the face masks, and then they deployed the face recognition cameras in Tbilisi. So it makes it easier for them to detect who is appearing at the rally and then order high fines.”

Last month fines went up ten-fold for blocking the road or disobeying the police and Tamar Oniani says in one day alone they received 150 calls from protesters who had been fined.

Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze has recently denounced the protesters as an “amorphous mass” and sarcastically thanked them for “replenishing the state budget” with heavy fines.

Tamar Oniani says the “judiciary is fully captured” and acts as one of the instruments against the demonstrators, who she says have been beaten in custody.

“They were tortured just for being part of the protest and being a supporter of Georgia’s European future.”

The government denies these allegations.

Since the protests began last November, hundreds of civil servants have lost their jobs after they signed petitions criticising the government’s decision to suspend talks with the EU.

“The government decided to cleanse the public sector of employees who were not loyal to them,” says Nini Lezhava, who was among those to lose their jobs.

She was in a senior position in Georgia’s parliamentary research centre, which had been tasked with providing unbiased reports for members of parliament and has since been abolished.

“They don’t need it anymore. They have their own policy and they do not want anyone with independent analytical capacity,” she says.

Nini says a similar “cleansing” has been taking place at the defence and justice ministries, and other government institutions: “It is happening in the entire public sector of Georgia”.

“They are trying to create another Russian satellite in this region. And that goes beyond Georgia and beyond the Black Sea, beyond the South Caucasus, because we see what is happening in the world. And that is a bigger geopolitical shift.”

In Chorvila, history teacher Temuri Kapanadze sees the government’s approach towards Russia very differently: “There are no friends and enemies forever. Yesterday’s enemy can become today’s friend.”

Hear more on this story here, on BBC World Service’s Assignment

Source link

Add a Comment