Sámi reindeer herders of northern Sweden adapt the animals’ grazing areas depending on the changing environment.Credit: Roberto Moiola/Sysaworld/Getty

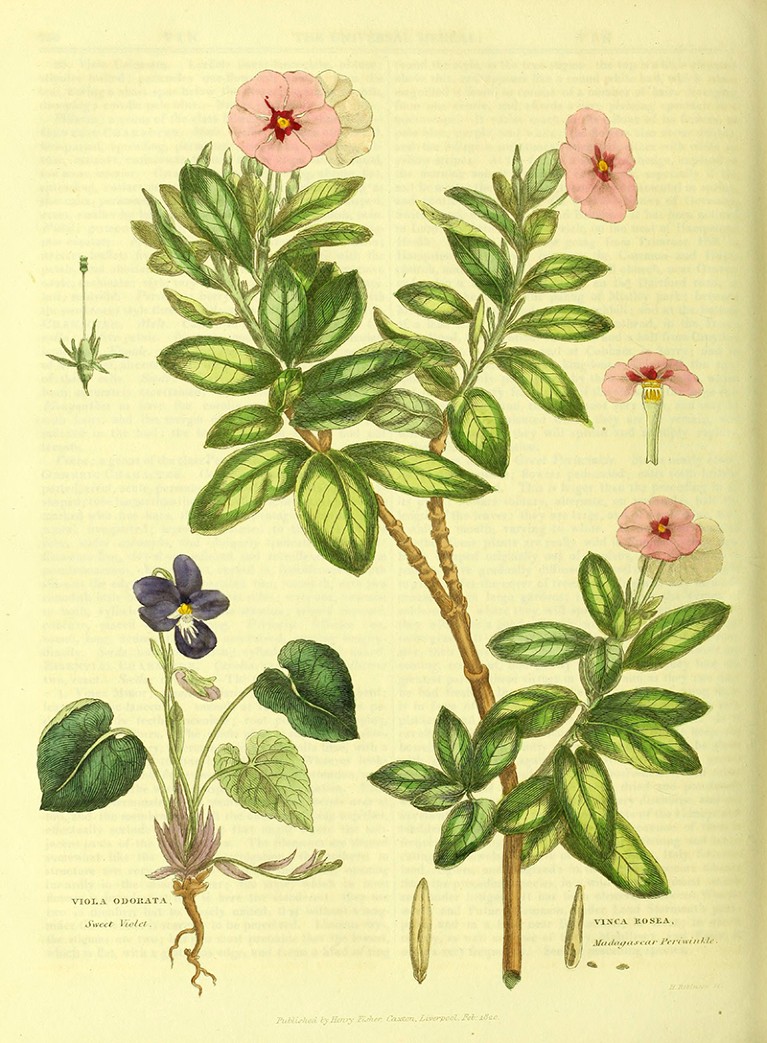

The Madagascar periwinkle packs a lot of healing power into its delicate pink flowers. Although native to the African island after which it is named, for centuries it has been cultivated and used in medicinal practices around the world — including Chinese, Ayurvedic, European and African traditions — commonly as a treatment for diabetes, but also for malaria, asthma, toothache and other maladies.

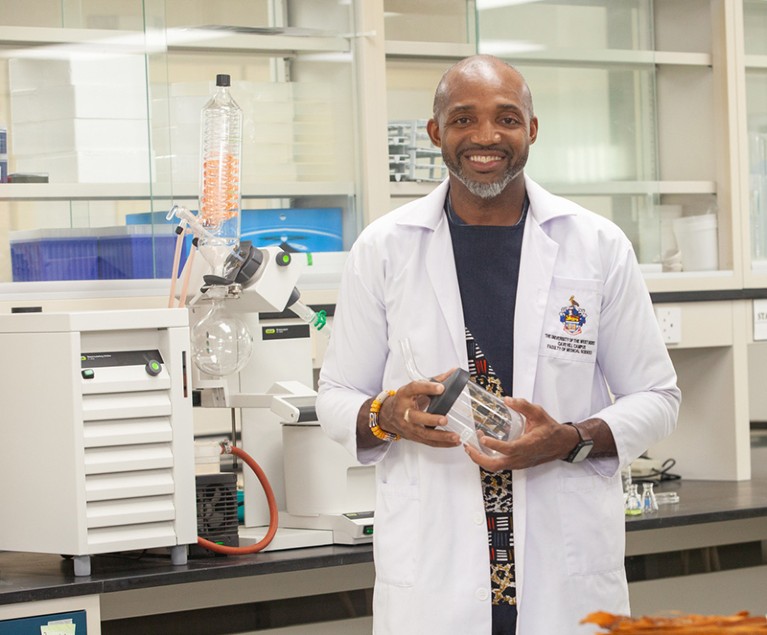

Extracts from the flower are used as a remedy for eye infections in the Caribbean, where Damian Cohall, a Jamaican-born ethnopharmacologist at the University of the West Indies in Cave Hill, Barbados, learnt of it through interviews with elder members of local communities. Research in his laboratory identified compounds in the plant that inhibit an enzyme that regulates insulin levels and could lead to treatments for type 2 diabetes (see go.nature.com/3djmhyr). “The fact that these anti-diabetic properties are known in traditional practices validates the Indigenous science that existed well before Western knowledge systems,” Cohall says.

How to support Indigenous Peoples on biodiversity: be rigorous with data

The case of the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) not only demonstrates the value of knowledge held by Indigenous and local communities, but also illustrates how this expertise has often been exploited. In the 1950s, Western researchers intrigued by the plant’s widespread use discovered that the vinca alkaloids that it contained could treat cancer. Drugs derived from these compounds are still sold worldwide today for huge profits, which Cohall says have not been shared equitably with the local communities where the knowledge originated.

Similar dynamics have played out repeatedly over the past 500 years or more, as Western science has become imposed as the dominant knowledge system around most of the globe. In the process, many alternative ways of understanding the world have been marginalized. “There has been for a long time, and there is still, a distrust of Indigenous knowledge among scientists,” says Marie Roué, an environmental anthropologist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris. She says that Indigenous knowledge is often dismissed because it incorporates religious or spiritual elements. It also tends to be passed on orally and through cultural traditions, making it hard to formalize in the manner prized by the Western empirical method.

However, Indigenous and local communities hold unique insights that can enhance people’s shared understanding of the natural world and inform attempts to protect it. Recognizing this, scientists such as Cohall and Roué are working in partnership with Indigenous and local groups to preserve and amplify these insights, integrate them into their own research and co-produce fresh knowledge with these communities.

Documenting and validating traditional medicine

Cohall has also identified anti-cancer compounds in the sarsaparilla plant (Smilax regelii). Currently, his lab is investigating the wound-healing properties of the Christmas candle plant (Senna alata), “inspired by information from a traditional healer in Ghana”, Cohall says.

The sweet violet (Viola odorata) and pink Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) have a long history of use for a range of maladies.Credit: Historic Illustrations/Alamy

Researchers who incorporate local traditions and Indigenous knowledge into their work need to be sensitive to a range of social and cultural factors, especially in the Caribbean. “It’s science,” Cohall says, “but at the same time it’s history, it’s globalization, it’s migration.”

Throughout history, various communities have settled, or been forced to settle, in the Caribbean. Each of these groups brought their traditions and culture and produced unique insights through their interactions with the natural environment. Sometimes the groups brought medicinal plants with them, which Cohall says might have happened with the periwinkle. But this knowledge has since been dismissed or suppressed. “A lot of those traditional Indigenous practices were pushed to the side because they were considered to be more primitive or not advanced or sophisticated, which led to a major loss of information,” Cohall says.

Weaving Indigenous knowledge into the scientific method

This loss continues today, in part because of the modern Westernized education system; “it might not directly suggest that you should not focus on Indigenous traditional practices,” Cohall says, “but it definitely emphasizes a different way of knowledge acquisition.” He also explains that urbanization has led more people to move to cities, away from the rural areas where they can experience nature and apply traditional practices. Although the Caribbean’s history is unique, these forces of suppression and cultural imposition are common threats to Indigenous and local knowledge around the globe.

Contextual understanding

Cohall says that he can investigate the efficacy of traditional medicine using Westernized lab methods because the basic aim of any medicine is the same: to treat illness safely and effectively. However, other forms of Indigenous and local knowledge fit less easily into different epistemological systems. Often, ways of understanding the environment are formed through direct experience of nature and can be altered by when, where and in whom the knowledge exists.

“In our Western world, nature and culture are separated, and science pretends to be capable of giving knowledge without taking into account culture. Indigenous knowledge is more holistic,” says Roué. She has spent decades working with the Sámi reindeer herders of northern Sweden and notes that these less tangible ways of knowing can be seen in the Sámi’s understanding of the lands that their reindeer graze on.

During winter, the Sámi’s reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) feed mainly on lichen that grows on the ground and is then covered by thick snow. This is dependent on a confluence of environmental factors, including the climate, soil and vegetation. If there’s no snow, the lichen is left exposed and is destroyed by the cold temperature and wind; if it rains, then a layer of ice can freeze on top of the lichen and prevent the reindeer from getting to it.

Reindeer in northern Sweden feed mainly on lichen that grows on the ground.Credit: Vasilisa Gagarina/Getty

The locations of good grazing areas therefore change constantly, which the Sámi have become sensitive to. This dynamic understanding of their environment is reflected in the Sámi word guohtun, which is most often translated as ‘pasture’. “They use ‘pasture’ because that’s the word in the other languages, but in their own language guohtun also encompasses how available the lichen is to the reindeer given the conditions today of the snow and wind,” says Roué. “They don’t speak about pasture like a botanist does -— as a permanent mix that is more or less good for an animal — they speak through their experience of ever-changing conditions.”

From exploitation to empowerment: how researchers can protect Indigenous peoples’ rights to own and control their data

Attempts to integrate this experiential and contextual local knowledge into scientific frameworks that prioritize stable truths can cause friction. For example, forestry companies have, with good intentions, attempted to work with the Sámi to map where reindeer graze and enable a productive dialogue between land users. But Roué says that the Sámi’s input has largely been ignored because the changeable concept of guohtun cannot be represented easily on maps. “That permanency doesn’t exist,” she says, “When you ask the Sámi, ‘What is the best place?’ or ‘When are you going to do the migration this year?’, they tend to tell you, ‘I don’t know, it depends,’ and Western people think the Sámi know nothing.”

Such thinking is, to some, infuriating. “I think that there’s an extraordinary arrogance that runs through many Euro-American knowledge systems,” says Luci Attala, a UK-based anthropologist and chair of the Tairona Heritage Trust, in Swansea, UK, which works to amplify the voices of the Indigenous Kogi people of northern Colombia. To her, researchers in the mainstream scientific establishment are culpable for the marginalization of Indigenous and local knowledge. “They’re part of the problem,” she says. “They’re part of the world that has spent years discounting other ways of being and assuming that their methodology is the one and only route to truth.”

The power of co-production

To tackle the issues that come with bridging distinct knowledge systems, Roué advocates scientists working with Indigenous and local groups to co-produce knowledge. For instance, the research of eco-anthropologist Samuel Roturier, who has worked with the Sámi for more than 15 years, shows how co-production can empower local communities and enrich conservation strategies.

Roturier, who works at AgroParisTech (part of Paris-Saclay University), has researched ways to increase forest biodiversity and lichen availability, especially through artificial lichen dispersal. The Sámi have to ensure that there are diverse habitats for their reindeer, so that there are always areas where the animals can graze during fluctuations in the weather, which are becoming more volatile because of climate change. But Roturier explains that the biodiversity of the forest is steadily decreasing “because of commercial forestry and the introduction of modern forest-management practices”.

Controlled burning is commonly used to manage forests around the world, but is not widely used by Swedish forestry companies. Although there is no evidence to suggest that the Sámi have traditionally used the technique, the idea that fire can benefit biodiversity is conserved in the Indigenous language. “There is a Sámi word, roavve, that means ‘a forest that has burnt in the past’ but also ‘a forest that is rich in lichen’,” says Roturier.

Pharmacologist Damian Cohall researches medicinal plants.Credit: Brian Elcock

Lars Nutti, a Sámi reindeer herder from the Sirges community, recognized the significance of this linguistic artefact. “Roavve is a description of an old sparse forest with good grazing for reindeer,” he says, “but recreating such forests is largely impossible with today’s policies.” After an expanse of forest burnt down near where Nutti lives, he approached Roturier with the idea of running a research project to investigate whether dispersing lichen in this area would result in healthier pastures. “And the results actually showed that it worked very well, beyond our expectations,” says Roturier.

Nutti has since co-authored 2 papers, the latest reporting on 11 years of the project1, and the findings offer insights that can inform forest conservation strategies. Discussions with forestry companies about further projects are under way, but Nutti is sceptical as to whether they will result in tangible progress. “We will probably have to continue to wait for some breakthrough with the forest companies to make large-scale attempts to restore lichen,” he says.

Source link

Add a Comment