Animals do not always need to be used in preclinical studies.Credit: Evgenyi Eg / Getty

While Catharine Krebs was working in a human-genetics laboratory during her PhD at the University of California, Los Angeles, there was a line that she got used to seeing at the end of papers: “These findings will need to be confirmed in vivo.“

What that usually means is in an animal model. “You just say it without even thinking, because you’ve been trained to think that that’s the next best line of investigation,” she reflects.

Krebs is now the medical-research programme manager for the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), a non-profit organization in Washington DC that advocates for alternatives to animal-based research.

In this role, she and other attendees at a 2022 workshop coined a term that helped to make sense of what she’d noticed as a researcher: animal-methods bias.

They define animal-methods bias as indicating “a reliance on or preference for animal-based methods despite the availability of potentially suitable non-animal-based methods”.

In 2023, Krebs and her co-authors at the PCRM and at Humane Society International Europe in Brussels, published the results of a survey of life-sciences researchers and peer reviewers1.

The authors note that the sample of 90 respondents was small, but provides preliminary evidence of animal-methods bias.

Some researchers felt that some of the requests from peer reviewers to add an animal-research component to their studies were unjustified and unnecessary, such as for researchers doing purely computational work.

“The issues are mostly with journals and funders,” Krebs says. In her experience, researchers who are using animal-free models are “extremely frustrated” by such pushback.

A spokeperson for Springer Nature, which publishes Nature, says: “As part of the peer-review process, our editors carefully evaluate requests by reviewers for animal studies and any arguments made against this by the authors.”

The spokeperson adds that at all times, its journal editors follow the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments guidelines 2.0, which were last updated in 20202. Nature is editorially independent of its publisher.

Animal research is not always king: researchers should explore the alternatives

Krebs and her colleagues are now following up with larger-scale research. One aspect Krebs is interested in investigating is whether the bias interacts with researchers’ experience. “The impact of animal-methods bias may be especially strong with early-career researchers,” Krebs hypothesizes. “If they undergo an experience where they feel like they have to use an animal research model to publish or get a grant or publish in a high-impact journal, then that just reinforces it, and it can set them on a career path where they’re using animals instead of other models that may more reliably mimic human biology but are not yet as common in the field.”

“We all know that our in vitro studies do not capture every aspect of biology or physiology,” says Abhijit Majumder, a chemical engineer at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay in Mumbai. “But at the same time, animal studies do not capture the many aspects of human physiology.” A commonly cited statistic is that about 90% of candidate drugs in early-stage clinical trials fail before reaching the market, in part owing to heavy reliance on animal models in preclinical research.

Majumder thinks that broader scientific acceptance of NAMs (an acronym that has been applied variously to “new approach methodologies”, “novel alternative methods”, “new alternative methods” and “non-animal models”) will take some time.

Funding opportunities opening up

Funding from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) has been crucial for Laura Sinclair, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Exeter, UK. She started out doing a non-funded PhD related to adipose tissue and diabetes. She then switched to a PhD on cellular ageing in an animal-research-free lab. She took advantage of an innovative funding model offered by the London-based charity Animal Free Research UK, which provided three years of funding for her PhD studentship, three years for her postdoc and three years for another fellowship. The stability has been very welcome for her as an early-career researcher, she says.

In general, Krebs says, NGO grants for animal-free research tend to be smaller than the longer-term, multimillion-dollar awards offered by government sources such as the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the world’s biggest funder of biomedical research.

Another change is the number of grants awarded to support the use of alternative methods. In 2021, alternative methods made up about 8% of competitive (non-clinical, non-invertebrate) awards disbursed by the NIH. In the early 1980s, that figure was essentially zero.

“It’s still small compared to the overall NIH funding,” acknowledges Danilo Tagle, director of the Office for Special Initiatives at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), an NIH institute based in Rockville, Maryland.

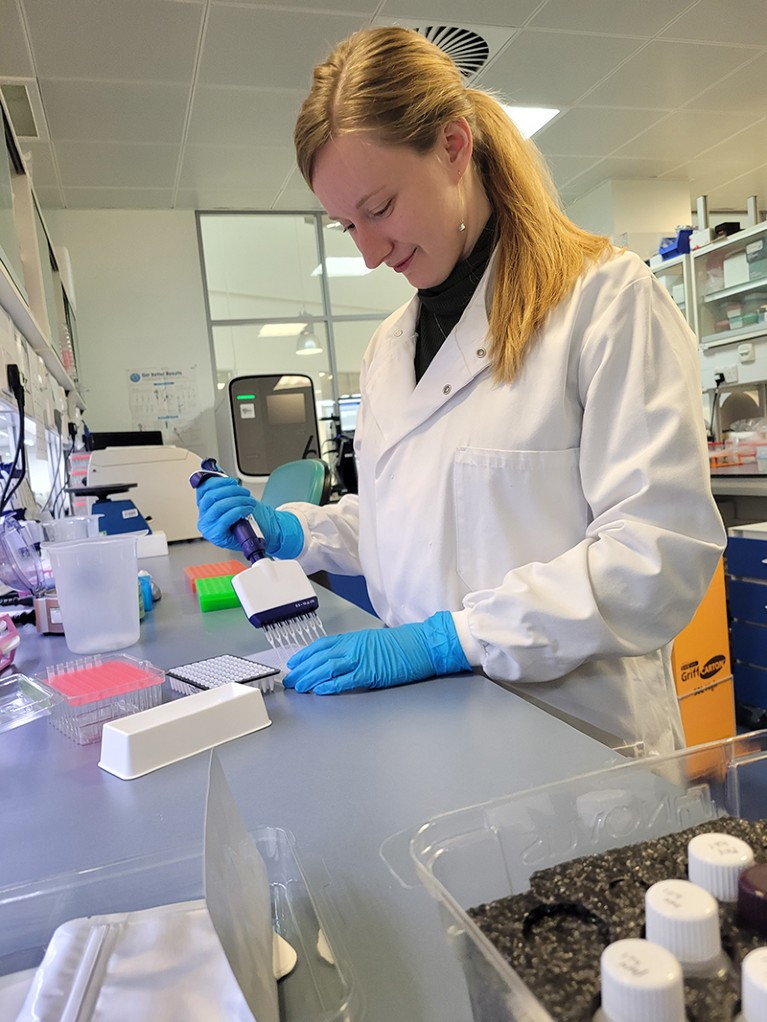

Laura Sinclair was grateful for an animal-free-research grant that gave her stability in the early stages of her career.Credit: Dr Laura R Sinclair

Tagle started his science career as a geneticist modelling human diseases in mice, which exposed him to some of the weaknesses in rodent models. He says that there’s been a gradual increase in NIH funding for NAMs, especially in the past decade.

In 2010, a European Union directive established an ambitious goal to fully replace live animals used for scientific purposes with non-animal methods such as organoids or computer simulations. However, the number of animals used in science in the EU barely moved between 2017 and 2022.

In terms of EU funding schemes and general acceptance of non-animal methods, there are more doors open to emerging researchers today, says Mathieu Vinken, who obtained his PhD in pharmaceutical sciences in 2006. Vinken is now a professor at the Free University of Brussels, with research interests including reducing the use of animals in space toxicology. His funding sources have included large EU grant programmes.

Overall, Majumder thinks that funders are further along than many scientists in being open to alternative models. For instance, a 2025 call for discovery research proposals from the Indian Council of Medical Research in New Delhi explicitly states that both animal and non-animal models are covered, and gives examples of non-animal methods.

Majumder and other scientists have found niches in which alternative methods are especially needed to plug research gaps. One example is investigating how safe medicines are likely to be during pregnancy because “most of the drugs, when they go through clinical trials, cannot be tested on pregnant women”, Majumder explains. For this, researchers are working on developing an organ-on-a-chip model, a microfluidic system that uses cultured cells to simulate the processes in various organs — in this case, the placenta.

Similarly, the NIH programme Complement Animal Research In Experimentation, established in 2024, is identifying areas in which animal models are lacking, including rare diseases and sepsis. The programme is a coordinated approach to funding NAMs across the NIH, says Tagle, who spoke to Nature’s careers team before the Trump administration paused some external communications and related activities at the organization.

“We’re looking at at least $30 million per year over the course of the next 10 years to develop NAMs,” Tagle says.

How a shift in research methodology could reduce animal use

Although there is uncertainty about the future of US government funding of biomedical research, Krebs thinks that there’s a case to be made that animal research can be quite wasteful, which could align with the new administration’s messaging about reducing government waste.

For the time being, duplicating research using different models — while more funders, regulators and scientists become comfortable with NAMs — can add time and expense.

“Essentially today we are in the cusp period where doing all this research has become expensive,” says Deepak Modi, a biologist focused on reproductive health at India’s National Institute for Research in Reproductive and Child Health in Mumbai, who collaborates with Majumder.

Modi thinks that in the future, some steps in the chain could be omitted, which would speed up the process and bring down costs without losing rigour. There might also be more “ready-to-play” organ-on-chip solutions once the technology matures, Modi says.

Sinclair thinks costs are coming down in response to consumer demand, noting a shift towards more synthetic, reproducible materials since she did her animal-free PhD. She and her colleagues have created a guide to working with tissue cultures that are relevant to humans and not derived from animals — the type of resource that would have been useful to her earlier in her career, she says.

From a funder’s perspective, value for money can be complex. “The translational implications have to be weighed in, because one can invest in animal models, but if the animal models are not necessarily human-relevant … then that’s a big waste in terms of time and resources,” says Tagle, who adds that with organs-on-chips, there are examples of moving from developing models to screening drugs and then going on to clinical trials much faster than when animal models were used. An example is researchers who used a lung tissue-chip to test the chemical azeliragon as a treatment for inflammatory lung diseases, an application that has moved on to phase III clinical trials.

Publication perils

Source link

Add a Comment