Whether their core business is search engines, social media, shopping or computing, data fuels the US tech behemoths — Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Nvidia — along with countless other companies. Now, though, it seems that the big-tech industry is increasingly focused on big energy.

These six US companies — the largest tech firms in the world, by market capitalization — are already substantial buyers of renewable electricity, but their needs are now being multiplied by the latest generation of artificial intelligence (AI) systems. In response, firms have been signing a flurry of deals with energy companies to establish new generating capacity.

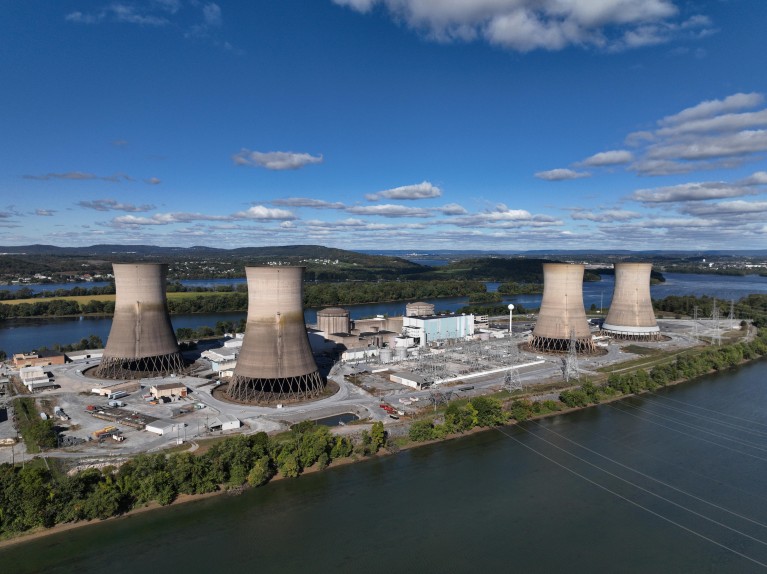

In 2024, for example, Microsoft announced that it had agreed on a 20-year deal to buy energy from a dormant nuclear plant at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania — the site of a nuclear accident in 1979 — which would reopen in 2028. Google (owned by Alphabet) and Amazon both revealed last year that they had made power purchase agreements (PPAs) with companies that plan to build a new generation of smaller nuclear plants known as small modular reactors (SMRs). Google and Meta are also investing in firms developing next-generation geothermal energy.

Nature Index 2025 Energy

These high-profile developments have garnered huge media attention, accompanied by speculation that they could help to accelerate the global shift to cleaner power. But many researchers point out that the big-tech industry is influencing the energy transition in much more significant ways: through their cloud computing services, by applying machine learning to the management of electricity supply and demand, and, above all, by harvesting — and exploiting — data about that energy.

“In general, it’s better to have them doing all this than actively opposing the transition,” says Silvia Weko, a sustainability researcher at the University of Erlangen–Nuremberg, in Germany, who studies the role of big tech in the energy business. But she’s not alone in a belief that there’s a risk that energy systems are also becoming too dependent on a handful of companies. “Once they have that monopoly, they can do whatever they want with it.”

The big-tech industry has a long history of building renewable-energy capacity to service its needs. Amazon, for example, owns roughly 25 gigawatts of its own installed capacity worldwide: mostly solar panels, with a smattering of wind. That alone is similar to the entire solar power capacity of the Netherlands. But the firm buys even more renewable energy from external suppliers through PPAs. These are long-term contracts to buy energy at a predetermined price, and Amazon has signed agreements that enable to it tap at least 33.6 gigawatts, according to the energy consultancy, BloombergNEF.

Sasha Luccioni, who studies the environmental impact of AI at US machine-learning company Hugging Face in New York City, says until about five years ago, this kind of approach had kept pace with big tech’s growing energy needs. “They were on track until generative AI came along,” Luccioni says. “I think that with the advent of these new, more energy-intensive models, the PPAs are not enough and now they’re turning to nuclear and other ways of dealing with it.”

In demand

Generative AI is a supersized form of machine learning that can be trained to recognize patterns within data in order to produce novel text, images and video. “It’s still this big pattern-recognition engine, but now these models are being trained on all of the internet,” says Raghavendra Selvan, a machine-learning researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

Training a model with billions of different parameters can take months of work at data centres that consume huge amounts of energy; and once the model is available for wider use, each query racks up further energy costs that can be ten times greater than a conventional web search.

Researchers say that those energy costs can be curbed. In January, for example, Chinese AI firm, DeepSeek, released a chatbot app based on its low-cost R1 model, which requires far less computing power to run than rivals developed by companies such as OpenAI in San Francisco, California.

Nevertheless, the rapid acceleration of AI means that finding a constant and reliable source of power for data centres is a growing problem, especially because solar and wind power are inherently intermittent.

In hot water

Next-generation geothermal systems might be one solution. Many conventional geothermal systems tap into reservoirs of hot water deep underground, drawing it to the surface to create steam that can drive turbines and generate electricity. But there are relatively few places on the planet that have the right combination of heat, fluid and permeable rocks, says Lauren Boyd, a geologist who heads the Geothermal Technologies Office at the US Department of Energy (DoE) in Washington DC.

Next-generation geothermal systems seek to overcome this limitation by engineering suitable subsurface conditions — either through a process akin to fracking, which uses high-pressure water and chemicals to fracture rock layers, or by drilling carefully guided boreholes deep underground. Both techniques create a route for cool water to be pumped underground, where it absorbs heat before returning to the surface for use in a power station. This should open up many more potential sites to turn geothermal energy into electrical power, and the DoE estimates that operators in the United States could develop 90–130 gigawatts of geothermal power capacity by 2050.

Part of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant will reopen to power Microsoft’s data centres.Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Boyd says that although these systems are likely to be more expensive to build than solar or wind, they offer other advantages beyond providing a more constant flow of power. They take up a lot less space, so they could be built in areas where land availability is a constraint, and they use materials and technologies that can be sourced within the United States — a key political consideration, given that China dominates the supply chain for materials used to generate solar power.

The combination of public and private funding for next-generation geothermal start-up companies such as Fervo Energy and Sage Geosystems, both based in Houston, Texas — which have partnerships with Google and Meta, respectively — helped to triple geothermal investment in the United States from 2023 to 2024. “Right now, the number of companies and start-ups in this space in the United States is pretty dramatic,” says Boyd. That puts the country in pole position in the race for next-generation geothermal power, although other nations — including France, Germany, Japan, Switzerland and the United Kingdom — have their own programmes.

Despite the enthusiasm, however, this new approach to geothermal power might take time before it has a noticeable impact on broader power supplies, and many experts agree that variable renewables linked to battery storage will likely be the backbone of decarbonization scenarios.

Going nuclear

Big tech’s investments in SMRs, meanwhile, are helping to bolster a technology that many governments hope will assist their decarbonization plans. Proponents say that these reactors could be built in factories using production-line techniques to create ‘modular’ units that will ultimately drive down the cost of nuclear power. Major firms already developing SMRs, such as Toshiba and Rolls Royce, are being joined by a parade of start-up companies that are trying different techniques and materials, hoping their designs will have an edge.

Yet behind the hype, there are no commercial SMRs currently in operation. “The press writes about them as if they already exist, as if we know that they’re cheap and they’re safe — but we don’t know any of that,” says Allison Macfarlane, director of the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and former chair of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. She doubts whether SMRs will offer any economic benefit over conventional nuclear reactors, and they might even generate more nuclear waste, adding to costs. “With nuclear, it’s always the price tag that kills it, and there’s nothing different about small modular reactors,” she says.

Macfarlane thinks that restarting dormant nuclear plants could offer a more promising strategy. That’s what utility company Constellation Energy in Baltimore, Maryland, plans to do with the plant it owns at Three Mile Island, in Pennsylvania, which will help to power Microsoft’s data centres. “That’s the one model that I see as being successful,” she says. However, she cautions that there are relatively few sites in the United States that would be suitable for that kind of make-over.

Power play

Weko and other researchers see big tech’s investments in these burgeoning technologies as more than a quest for energy. Instead, they say it is part of a broader business strategy to play pivotal roles in every aspect of the energy transition, from individual homes to national grids.

Many homeowners already use Amazon’s cloud-based AI assistant Alexa to manage their domestic energy use. But Weko has detailed (S. Weko Rev. Political Econ. https://doi.org/n8wk; 2024) how global energy-related companies also depend on Amazon Web Services (AWS), the biggest cloud computing company in the world with around 30% of market share and revenues topping US$75 billion in 2022. AWS servers help to manage data about the supply, demand and storage of energy, weather patterns, and a host of other variables. AWS also uses machine-learning systems to analyse those kinds of data, to forecast and potentially optimize renewable-energy production. “If you increase the amount of solar and wind on the grid, then it just gets more complex to control, because you need to match supply and demand,” says Lynn Kaack, who studies the relationship between AI and climate change at the Hertie School, a university in Berlin, and is also the co-founder of non-governmental organization Climate Change AI.

Source link

Add a Comment